ASCAP – Mike Love’s Endless Summer of Love

Mike Love’s Endless Summer of Love

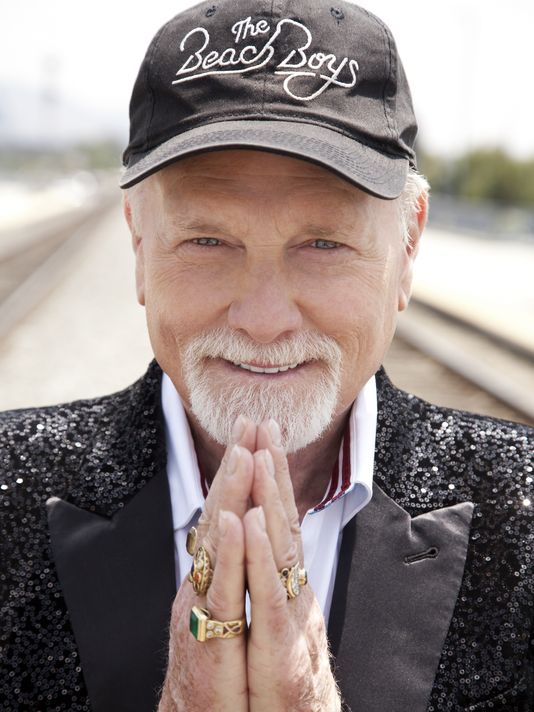

Half a century after he co-wrote “Good Vibrations,” new ASCAP member Mike Love still finds inspiration in the music and legacy of The Beach Boys

By Etan Rosenbloom, Director & Deputy Editor, Marketing + Communications

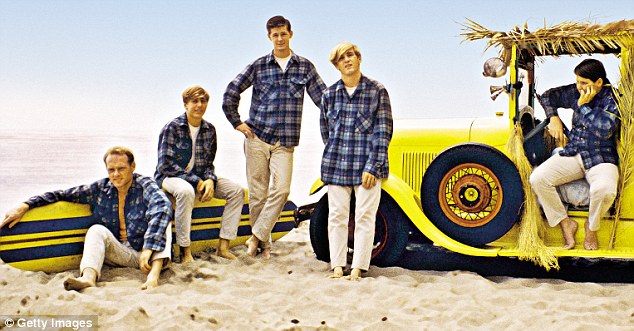

IN THE LATE 1840s, hundreds of thousands of hopeful pioneers began flocking to California, lured by the promise of gold and sunshine. A century later, The Beach Boys inspired their own California Dream. Their songs are more than just radio staples, passed down from one generation to the next. They also defined an entire narrative that still captures the world’s imagination today – the vision of California as a land of good luck and great weather, unlimited possibility and endless youth.

One of the primary architects of that musical mythos is Mike Love, the lyricist for many of The Beach Boys’ signature songs. He co-wrote nearly all of their Top 10 hits – including “Fun Fun Fun,” “California Girls,” “I Get Around,” “Help Me Rhonda,” “Kokomo” and “Good Vibrations” – and sang lead or co-lead on many more.

Now 75 years old, Love is as busy as ever, and shows no signs of slowing down. He still plays well over 100 shows a year with The Beach Boys. On September 14th, Love and The Beach Boys will play New York’s Central Park’s SummerStage – just a day after Love’s memoir Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy is officially released.

Shortly after Mike Love became an ASCAP member (the official date was during the first week of summer, naturally), we asked what motivates him to keep spreading the sunshine gospel that he helped write, more than 50 years ago.

********

What was the first song you wrote? Did it take some work before you were writing songs you were really proud of?

My first song I wrote when I was 10 years old, titled “The Old Soldier.” It was about a past life impression which was unusual at that age, or maybe natural, because you are more sensitive at that age before life experiences take over. The first Beach Boys song which started our careers was “Surfin’,” soon to be followed by “Surfin’ Safari,” which became our first successful recording. I was very proud.

Who were some of your songwriting heroes when The Beach Boys were first coming up?

Chuck Berry was an enormous influence on my writing style, primarily the up-tempo recordings that I wrote.

The early Beach Boys songs paint a carefree picture of life in Southern California: sun, surfing, cars and girls. Was that a pretty accurate depiction of what you and the other Beach Boys were into when you were growing up?

The advertising industry calls it “heightened reality.” We took those impressions from our Southern California upbringing, and I crafted the lyrics to describe our life experiences at the time.

When you used to write with Brian Wilson, did he usually set your lyrics as written, or was there a lot of back and forth leading up to the final version?

Our songwriting partnership was ideal. Brian would focus primarily on melodies, harmonies, chord progressions and backing/instrumental tracks, leaving me free to find the lyrics and concepts that resonated with the music. For all the hits we had, Brian would rely on me for the concepts and lyrics as I would rely upon him for the production.

2016 marks the 50th anniversary of “Good Vibrations.” Its lyrics are more impressionistic, less straightforward than many of your earlier songs. Did you have a sense of what the song would become when you were writing that lyric?

What I had was a sense of the mood of time of 1966. Flower power and the hippie movement were in full swing, particularly in California. Whereas many of our earlier songs focused on our outer objective experience peculiar to Southern California, “Good Vibrations” dealt with subjective, intangible feelings descriptive of an idealized vision of a girl who was all about Peace and Love…the epitome of flower power…“She goes with me to a Blossom World we find…”

Beach Boys are one of those quintessential vocal groups. How did the sound of your voices impact the lyrics that you wrote? Were you ever inspired to use words because of the way they sounded when you harmonized, or change a lyric that didn’t sit quite right when you all sang them together?

The blend of the harmonies was the thing that was complementary to the instrumental aspect of the music. At least in my experience, it didn’t have much to do with the lyrics. The lyrics or lead were more impacted by the production of the song like the tempo, the feeling that the music evoked. For example, the haunting melody of “The Warmth of the Sun” — the mood of the music influenced the lyrics. Sometimes I would sit alone listening to the track for hours on end in order to immerse myself in the mood and feeling of the music, which would then give rise to the lyrical message.

Your memoir Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy is coming out soon. With more than 50 years of anecdotes to choose from, how did you decide what would make it in?

I felt that my memoir should primarily focus on some of the things I felt essential to share with respect to The Beach Boys career, hence “My Life as a Beach Boy.” There are many people and experiences that were very impactful and important to me throughout the course of my life, but for this autobiography, I felt we should focus on events relative to The Beach Boys career from my perspective.

Do you still find time to write new music despite your non-stop touring schedule?

As a matter of fact, I’ve never stopped writing music. I have several dozen unreleased songs and poems.

What has touring the world taught you about what you and The Beach Boys have achieved?

International touring has never ceased to amaze me. To be in front of a crowd of 30,000 people in Japan and have them erupt in a chorus of classic hooks of our songs. And performing in Germany, France and Scandinavia, where language differences are transcended by our music, is mind blowing. Nothing in my life experience in foreign performances could match the impact of our concerts in Czechoslovakia…I talk about it in the book.

Post-Pet Sounds, you and the other Beach Boys began writing songs about spirituality, meditation, the environment…Is it still important to you to spread a message with your music? What message matters most to you now?

Yes, it is very important to me to bring attention to the challenges that face our environment. I wrote a song with Terry Melcher titled “Summer in Paradise” which we currently perform during each performance. Al Jardine and I wrote a song titled “All This Is That” which speaks to our shared spiritual ideas and beliefs…Christopher Cross has longed claimed this as his favorite Beach Boys song.

As a new ASCAP member, what inspires you about ASCAP’s mission?

I laud the efforts of ASCAP and its protection of songwriters’ and publishers’ art. I look forward to becoming very involved with ASCAP where I might be a useful voice to champion the initiatives of our songwriting community.

From Katy Perry to Best Coast, so many younger musicians have sampled your songs, or been majorly influenced by The Beach Boys. How does it feel to hear new generations re-interpreting and taking so much inspiration from your music?

I feel honored that younger artists hold The Beach Boys in such high regard, such as Foster the People who performed “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” and Maroon 5 who performed “Surfer Girl” in 2012 with us at The Grammys.

And John Stamos has played a significant role exposing The Beach Boys to much younger generations through our appearances on Full House. As a kid, Stamos would ride his bike past my grandparents’ home and peer through the windows, gazing at our gold albums hanging on their walls. And to this day, he joins on us on stage, as his love of this music endures.

Do you relate differently to “Fun Fun Fun,” “California Girls,” “I Get Around” and all the rest of the classics you wrote after singing them for so many people over five decades?

I don’t think I relate to them differently, but I’m awed by the continued timeless popularity of these songs. These songs have become a part of the American Songbook.

‘One of the Charles Manson murderer gang BABYSAT my two children’, says Beach Boys star Mike Love

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/event/article-3761744/One-Charles-Manson-s-murderers-gang-babysat-two-children-says-Beach-Boys-star-Mike-Love.html#comments

In today’s Event magazine, Love recalls his horror when he realised the children had been left with Susan Atkins, later convicted for her role in the notorious Manson murder spree of 1969.

In an extract from his autobiography, Love writes: ‘Atkins was convicted of participating in eight murders and was sentenced to death. And she was our babysitter!’

At the time, Love was separated from his wife and mother of his children, Suzanne, who was involved with his cousin and fellow band member Dennis Wilson. Atkins had landed the job of babysitter after Wilson fell under the spell of Manson in the summer of 1968.

Love, who had co-founded the group in the 1960s, recalls how Manson and his debauched followers began taking over every aspect of his cousin’s life.

Manson, then 33, had already served time for armed robbery and car theft but harboured dreams of being a rock star and believed Wilson could put him on the road to fame and fortune.

Love recalls how the ‘guileless’ Wilson gave Manson and his female followers control over his home, his credit cards and even his Mercedes.

Atkins’s death sentence for her role in the murder spree was commuted to life imprisonment and she died behind bars in 2009.

Manson is now 81 and remains imprisoned in America.

When The Beach Boys came home from the road in 1966, we knew instantly that things were getting weird.

Our leader, Brian Wilson, had erected a tent in his house – red and maroon with gold brocade – built in his den, with hookah pipes for marijuana. He’d had a carpenter construct an 18-inch-high sandbox around the grand piano, filled with eight tons of sand, allowing Brian to feel as if he were writing music at the beach – which was strange, because Brian didn’t like the beach.

He’d removed the furniture from his living room and put down workout mats, which were good in theory if not in practice – Brian’s weight continued to balloon.

Recording a song in our absence called Mrs O’Leary’s Cow – after the animal that started Chicago’s deadly fire in 1871 – he burned wood in buckets and had the musicians play wearing red fire hats. When a building across the street from the studio burned down a few days later, a panicked Brian thought it was the fault of his song.

The problem, of course, was the drugs – not just LSD, but large amounts of marijuana, hashish and amphetamines.

We had seen signs that something was amiss for some time. On a flight to Houston in December 1964, Brian had an extreme panic attack, crying and yelling, ‘I just can’t take it!’ In July 1965, he pulled into a gas station and rammed his car repeatedly into a 7-Up machine, laughing all the while.

By 1966, Brian’s wife Marilyn was as uneasy as we were. When Brian was writing the song Love To Say Dada, he asked her to buy him a baby bottle and fill it with chocolate milk, which he would drink as he wrote. ‘I slept with one eye open because I never knew what he was going to do,’ she later said of her husband’s alarming behaviour. ‘He was like a wild man.’

The Beach Boys had been the first boy band – a group of young guys who played pop songs for teenagers, taking ‘the California sound’ to the world. Brian was our musical genius, although as the lead singer, I had co-written some of our biggest hits, including Surfin’ USA, I Get Around and California Girls.

But by 1966 we were all under a lot of pressure, trying to keep pace with The Beatles, trying to satisfy the label, trying to become a global band – and 24-year-old Brian felt it the most.

While we toured, Brian was working on an ambitious new album known as Smile, envisioned as a ‘teenage symphony to God’. The music was bizarre and beautiful, but I didn’t understand a lot of the words – I thought they had been influenced by the drugs. My complaints were ignored.

When it was time for us to provide vocals, Brian had us lie on our backs and make strange guttural sounds. He drained his swimming pool, put a mic at the bottom, and had us sing. For the song Heroes And Villains, we sang through our noses. These are not pleasant memories for any of us.

‘Brian degraded us, made us lie down for hours and make barnyard noises, demoralised us, freaked us out,’ our bass player Bruce Johnston recalled in 1995. ‘He was stoned and laughing. We didn’t really know what was happening to him.’

It was certainly a long way from singing with my three cousins, Brian, Dennis and Carl Wilson, as a child at my mother’s Christmas parties. The first time I saw Brian perform, he was on Grandma Wilson’s lap and singing Danny Boy. I can still see him and hear him: his voice was crystal.

As we got older, we never had a big meeting and decided to create a band – it was more of a natural evolution. On one of our youthful fishing trips, Dennis and I got talking about the surfing craze and why it made sense to do a surfing song. He went home all fired up and told Brian about it. Brian didn’t surf and knew little about it, but the idea intrigued him. With Brian’s friend Al Jardine on board, we just coalesced, singing in the Wilsons’ music room.

If Brian was the musical dreamer and youngster Carl the little angel, middle brother Dennis was the furious rebel of the Wilson family, which was ruled by father Murry, a blunt, pipe-smoking bull of a man who managed the group in our early years.

Dennis craved anything that might be dangerous. As a teenager, he used a BB gun to shatter windows from passing cars. As an adult, while flying on a commuter plane into New York, he told the pilot to bisect the Twin Towers, or he’d be fired. Dennis thought it’d be fun to buzz them. (The pilot refused and kept his job.)

He had an evil sense of humour, too. Dennis once showed up at our early guitarist David Marks’ house with a jar of ashes and tears in his eyes, jabbering that Brian had died in a house fire and the ashes were all that remained. David believed him until Dennis burst into laughter.

Uncle Murry had dreamed of his own career in music, which he eventually channelled through his sons. But he also dominated and bullied them. One of his more ghastly tactics was to remove his glass eye and force his boys to stare into the empty socket.

We started making demos, and an early song, Surfin’ Safari, struck Capitol Records as a sure hit. Uncle Murry did the deal.

‘What do you want, Mr Wilson?’

Uncle Murry opened his wallet, showed it was empty, and said, ‘I just paid the boys my last $1,000. I need $300.’

‘Is that all you want?’ they asked.

‘$300,’ he said. The record company man later said he had the authority to sign us for $50,000, so he got us pretty cheap.

Even though I was the oldest in the group, I don’t believe I was better prepared for handling our rapid success. One day you’re sweating in your father’s sheet metal factory, and the next day, you’re singing before a thousand girls screaming at the top of their lungs. Dennis said the first time he heard that sound, he thought there was a fire.

It felt good to be a rock star, I can’t deny that. My wife Frannie was pregnant with our second child, but I was not prepared to be a father or a husband. I suddenly had the life of a young rock star, and that meant yielding to every sexual impulse and sleeping with as many women as possible. I was like a kid in a candy store, and there was a lot of candy.

On one of my weekend jaunts to Hawaii I met a beautiful young Japanese woman who sold real estate and though I wasn’t looking for property, she invited me to her apartment for the night. The next day, I met a gorgeous Filipina woman. At lunch, the maître d’ told us that her boyfriend was looking for her, so we escaped through the kitchen and spent the rest of the afternoon in my hotel room.

That evening I bumped into an attractive young woman whom I knew from Dallas, and well, you know the rest. This delirious circuit, of three girls and copious booze, went on for a couple of days – and then ended abruptly with a shame-faced trip to the clinic.

For a bunch of California kids, this was a strange, exciting, bewildering time. And as our fame grew, tensions materialised in the band, especially between Dennis and me. It’s not that he and I were like oil and water. We were like burning oil and burning oil.

We had water pistols and liked to goof around with them, but in Des Moines, Dennis filled one with urine and fired it at me in the airport lounge. I told him to cut it out, and we just mauled each other. He got me in a headlock. I sank my teeth into his wrist.

Eventually, Dennis stood over me. He was preparing to smash me with his fist but his legs were spread and I was ready to drive my heel into his groin. ‘You hit me and you’ll never have kids,’ I snarled. We looked each other in the eye. And we realised we were still cousins, still bandmates, still booked to do our next show in a couple of nights.

After Franny and I inevitably split, I lived with Dennis for a while in Hermosa Beach in Los Angeles. He and I had our battles over the years – about women, about his drug use and lifestyle. But no one ever said Dennis didn’t have fun. The apartment was a non-stop party pad – I’d come home sometimes and not recognise half the people there. I’m not sure Dennis did either.

Onstage, behind the drums, Dennis was nearly impossible to upstage. As one woman told me years later, ‘Dennis could just move his head, and women’s zippers would drop.’

While Dennis and I were living the rock ’n’ roll life, Brian was learning his craft, and it didn’t take long to see his evolution as a producer. Within months of our first hit, he had more confidence and would no longer tolerate his father’s meddling. When Murry showed up at the studio, Brian told him to leave. He told his dad he was fired as producer.

‘If I don’t produce these records, you’re going out of business,’ Murry said. ‘You guys are going down the tubes in six months!’

Brian prevailed, but Murry still managed us, and he also controlled our songwriting credits. So when I looked at the sleeve of our second record, I was surprised to find that I was not credited on two songs I had co-written with Brian – Catch A Wave and Hawaii.

I asked Brian about it, and he said his father would get it done. I trusted Brian and assumed that Uncle Murry would take care of the details. This was, after all, a family business. Back on the road, the wild times continued. I remember an opening act in Australia and New Zealand called the Joy Boys. They had a spellbinding effect on young women and liked to invite their most attractive groupies to something called a Shalomanakee. The invitation was extended to us, and when we arrived, there were the Joy Boys and their lady friends, all in various stages of undress. We had walked into our first Australian orgy.

Carl and I had no interest in group sex, but that wasn’t all there was to it. A naked Joy Boy rolled up a newspaper into a funnel, lit the big end on fire, and stuck the other end in his buttocks. Then he started waltzing around the room – they called this ‘the dance of the flames’. Dennis and I later imported our own unique interpretation to the Hawaiian Islands, though not without a fire extinguisher nearby.

Murry came with us on that tour, too. He had bullied Brian for years, but he increasingly called into question his manhood.

‘If you were a man, you would tell Mike to stand closer to the microphone.’

‘If you were a man, you would tell Carl and Dennis to brush up on their harmonies.’

Enough was enough. After we got back from Australia, we took a vote on whether Murry should remain as our manager. It was five-zero to dismiss. My uncle was only 46 years old, but the episode sent his life into a spiral. Aunt Audree later said that his dismissal destroyed him – he stayed in bed for weeks.

A couple of months later, in April of 1964, he appeared at a studio session, inflamed and inebriated, and approached Brian, who was at the control board.

‘Get out of the way,’ Murry huffed. ‘Get out of my way for a minute.’

Brian had a hard time standing up to his father, but this time he did. ‘No! You get out of my way!’ He shoved his dad, who went sprawling backward. That was the only time I saw Brian defy him physically, and Murry, defeated, left the studio.

Within Brian, too, a storm was brewing. We already knew that he didn’t like the road, and his ongoing battles with his father took an emotional toll. In January 1965, he announced to the band that he wouldn’t be touring with us any more.

He later told a journalist that he was boiling with resentment for both Phil Spector and The Beatles, and to compete with them, he wanted to sit at the piano and write songs while we played and promoted them across the country.

But there were other concerns. In a hotel room, as early as 1964, I’d seen a syringe and other drug paraphernalia in Brian’s toiletry kit. He was the last person I imagined getting involved in drugs. In high school, he didn’t even drink or smoke. But Brian’s drug abuse would soon be evident to all of us.

By 1965 he was taking one LSD pill a day and smoking three or four marijuana cigarettes. He credits LSD with inspiring songs like California Girls and Good Vibrations, and the album Pet Sounds. What I know is that Brian was healthy before he took the drugs, and then he wasn’t.

I was outspoken about the drugs and my contempt for Brian’s hipster friends who introduced him to them, so I took the brunt of their scorn. Later, I would be cast, with the other Beach Boys, as a villain of the piece for ‘being negative towards Brian’s experimentation’. I learned long ago that if you’re going to be in the spotlight, either you develop a thick skin or you find another job.

Brian eventually scrapped the Smile album. Doctors would diagnose him with a variety of mental illnesses, including depression, paranoid schizophrenia, auditory hallucinations and organic personality disorder. It took decades for my cousin to get his life back on track, and he was never truly the same.

In Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, a character is asked how he went bankrupt. ‘Two ways,’ he says. ‘Gradually and then suddenly.’ The Beach Boys’ fall from the top happened in a similar fashion.

FBI agents arrested Carl for evading the draft. We had a disastrous tour of the UK – the British Musicians’ Union forbade us from using the four extra musicians we had brought from the States, so we couldn’t recreate the studio sounds onstage. Smile’s replacement, Smiley Smile, was a baffling departure from everything we’d ever done, pretty much alienating our entire market. Dennis, meanwhile, found a troubling new guru named Charles Manson.

And in 1969, we learned that our entire catalogue of songs – 140 to 150 of them, including about 80 I had co-written, though I had received credit on only a fraction of them – was to be sold. A&M agreed to pay $700,000 for the entire catalogue. And the payment was going, not to the band, but to Uncle Murry. In cash.

I drove to Brian’s house in Bel Air to see if he knew what was going on. At the time, Brian was not in good shape. He was using cocaine and living in the chauffeur’s quarters of his home while his wife Marilyn slept in the bedroom.

I reached his house, stormed into his room and asked what happened with our songs.

‘My dad f***ed us,’ he said.

‘Yeah, no s***.’

For the deal to go through, the agreement had to be signed by Brian, Dennis, Carl, Al, and me. I complained to the lawyers that songs like California Girls, I Get Around and Surfin’ USA, while co-written by me, had never been credited. If I signed, I’d lose the chance to claim them. But if I didn’t, he said, I might lose credit for Good Vibrations, Surfin’ Safari and The Warmth Of The Sun, which did bear my name.

What could I do? I had to sign the agreement to retain what I had. Everyone else signed too, and we lost all we had created.

It wasn’t until 1994, as I faced Brian in a courtroom, that jurors ruled that I deserved credit on 35 Beach Boys songs that had been solely credited to Brian for decades, leaving him facing potential damages of between $58m and $342m.

I had no interest in crushing my cousin, and it wasn’t about the money anyway. It was about getting credit for my songs. I proposed that he give me $5m and we move on. Brian agreed.

Years passed. Dennis had drowned in 1983, and Carl died from cancer in 1998, but Brian and I continued to communicate, and The Beach Boys continued to tour while Brian pursued a solo career.

In 2012, Brian, Al, David Marks and I reunited as The Beach Boys for a tour and a new album. The whole experience was bittersweet for me. The concerts were amazing, and I was grateful to play again with all the living Beach Boys. Brian and I never had a cross word, but there were tensions between our camps.

The reunion was never meant to be permanent – it wasn’t feasible logistically or economically. But after the shows, when I issued a press release to announce its end, the media backlash was swift and devastating: I had fired Brian Wilson from The Beach Boys. This triggered death threats, by mail and phone, which we had to take to the authorities.

I didn’t care for the vilification at the end; I’m used it. For those who believe Brian walks on water, I will always be the Antichrist.

Edited extract from ‘Good Vibrations: My Life As A Beach Boy’ by Mike Love, published by Faber & Faber on September 15, priced £20. Offer price £15 (25% discount) until September 11, 2016. Order at mailbookshop.co.uk or call 0844 571 0640, p&p is free on orders over £15

Mike Love: My life as a Beach Boy

http://www.express.co.uk/celebrity-news/705982/Mike-Love-My-life-as-Beach-Boy

For more than half a century the Beach Boys have reigned as America’s ebullient surf music kings. Their four-part harmonies evoke the sounds of an eternal summer with classic hits including California Girls, Surfin’ USA, I Get Around and Help Me, Rhonda.

But lead singer Mike Love, in his new memoir Good Vibrations, reveals a band often at war, torn by booze, drugs and betrayal, their musical genius tormented by madness – and members haunted by the homicidal Manson family. “There were dark times and questionable behaviour,” Love tells the Daily Express with heavy understatement.

“But being a Beach Boy was something special. For all the strife and turmoil the music has bonded us together.” Yet good vibrations were often hard to find in the band, which comprised brothers Brian, Dennis and Carl Wilson, their cousin Mike Love and schoolmate Al Jardine.

Brian was the band’s musical mastermind and Love wrote the lyrics to many of their greatest hits but LSD use unleashed Brian’s inner demons. “When Brian went off the deep end it was like losing my best friend,” says Love. “Brian’s confidence waned, the paranoia set in and the unravelling began.”

Brian confesses: “It ruined me… caused permanent damage. I’d take some psychedelic drugs and then about a week after that I started hearing voices… all day, every day – and I can’t get them out. Every few minutes the voices say something derogatory to me.” The voices haunt him still but in the 1960s he sought respite by diving deeper into drugs.

Love explains: “Doctors would diagnose Brian with a variety of mental illnesses, including depression, paranoid schizophrenia, auditory hallucinations and organic personality disorder.” His weight ballooned to over 21 stone and his behaviour became increasingly erratic.

He trucked eight tons of sand into his living room “allowing Brian to feel as if he were writing music at the beach which was strange because Brian didn’t like the beach”, says Love. He drained his pool so they could sing at the bottom.

Dennis Wilson was also lured into drugs and forged a dangerous friendship with future massmurdering cult leader Charles Manson. “Manson’s blending of psychedelics, sexual servants, rock music and new-age rhetoric was too much for Dennis to resist,” says Love. Dennis had picked up two female hitchhikers who turned out to be part of the Manson “family”.

“Dennis’ appetite for sex was insatiable,” says Love. “Too much was never enough.” The girls moved into Dennis’ mansion in 1968, bringing Charles Manson with them, using the Beach Boy’s credit cards, taking his clothes, eating his food, even driving his Mercedes.

A convicted armed robber and car thief, Manson was also an aspiring rock star. He wrote songs with Dennis and even had one recorded by the Beach Boys. Love recalls a dinner where Manson introduced his female followers – all naked. “He started passing out LSD tabs and orchestrating sex partners. I love the female form but this was too much even for me.”

Love went to take a shower and in with him stepped Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme who was later jailed for attempting to shoot president Gerald Ford. Love is still “horrified” that he allowed Manson follower Susan Atkins to babysit his children, weeks before she stabbed pregnant actress Sharon Tate to death and wrote “PIG” in Tate’s blood on her front door.

Too much was never enough

Valium, cocaine and alcohol were found in his blood. “I felt sadness but not surprise,” says Love. Carl died of lung cancer in 1998, aged 51. Brian also fell under the spell of Svengali-like therapist Dr Eugene Landy, who cut the musician off from family and friends, controlled his fortune and became his manager. A lawsuit by the band exposed Landy, who “left him in worse shape than when he found him”, says Love.

Yet Landy was just another dominating father-figure for Brian. When the Beach Boys formed in 1961 they were under the sadistic thumb of their manager, family patriarch Murry Wilson, a frustrated musician who regularly beat his sons. Murry forbade drugs and alcohol, fined the boys $200 for swearing, imposed curfews, produced their records and controlled their money, says Love.

After three abusive years the band fired Murry as manager. Brian took over as producer but proved a harsh taskmaster. Love admits: “I named Brian ‘the Stalin of the studio’.” Love wrote the lyrics for Good Vibrations in the 20 minutes it took him to drive to the recording studio but the song took 22 recording sessions for perfectionist Brian.

“At the time it was certainly the most expensive single ever produced,” says Love. Though Love co-wrote more than half the Beach Boys songs he received credit on barely a handful, despite Brian’s repeated promises to correct the mistake. “It cost me millions of dollars in lost royalties,” says Love. “It was a tragedy.” He sued in 1992 and under oath Brian admitted that Love was his frequent writing partner.

Love could have been awarded up to $342million in damages but settled for just $5million from Brian. “Before the trial I was receiving about $75,000 a year in songwriter royalties. After the trial the amount jumped to over $1million a year.” Amid the group’s debauchery Love found peace studying transcendental meditation with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, travelling to his ashram in India where he found himself alongside The Beatles, Donovan and Mia Farrow.

Love and Brian remained friends despite their lawsuits and even performed together for the Beach Boys’ 50th anniversary tour in 2011. But after a falling out Love hasn’t seen him since and admits: “I don’t know if Brian and I will ever play together in another concert or share a meal together or even have a conversation.”

Love laments their estrangement, saying: “If Brian and I could just be left alone in a room with a piano that would be great – but others always intervene. Could we get together again? I never say never. I miss him.” Yet a revamped Beach Boys continue to thrive without Brian.

Love says: “The band has never been in greater demand – for each invitation we accept we turn down two to three.” Last year the band played 175 concerts in eight countries, including two sold-out shows at London’s Royal Albert Hall. Their music catalogue today is worth about £76million. And Love isn’t ready to quit yet.

Though he’s 75 with four grandchildren he says: “The music itself never gets old.”

• To pre-order Good Vibrations, by Mike Love (published September 15 by Faber & Faber, £20) call the Express Bookshop with card details on 01872 562310. Or send a cheque made out to Express Bookshop to Mike Love Offer, PO Box 200, Falmouth, Cornwall TR11 4WJ or visit expressbookshop.com UK delivery is free.

It’s a proper, no-holds-barred romp through the life and times of the greatest US rock band to surf the planet.

Good Vibrations: My Life As A Beach Boy by Mike Love (Faber & Faber, £20)

The Beach Boys captured the California dream in their songs about an endless summer of surfing, girls and cruising around in a convertible. But the initial burst of hit singles – Surfin’ USA, Surfin’ Safari, Surfer Girl – that established the band’s clean-cut, smiley wholesomeness became a burden. Their innumerable compilation records played on the same image long after they had moved on musically, culturally, politically and personally.

As one of the original members and cousin to the three Wilson brothers Carl, Dennis and Brian, Mike Love gives an overview of more than 50 years in the music business. He is both involved and detached, an insider/outsider whose commitment to the group and its members has been notoriously capricious.

Much of his tale is uplifting, especially stories of songwriting with Brian Wilson, combining his honed and honeyed lyrics with the troubled genius whose musical innovation saw him compared to Mozart.

Love was the most commercially minded of the group and acted as a corrective to Brian Wilson’s infinite experimentation (yet he was the first to embrace Transcendental Meditation).

But he doesn’t shy away from the less palatable aspects of a tale that includes drugs, girls, fights, divorces and endless court battles over royalty payments.

Regarded as the Beach Boy you love to hate, Love is candid about his own status: “For those who believe that Brian walks on water, I will always be the Antichrist.”

Love gives his side of stories that have been told and retold including tales of the Wilsons’ violent father Murry, who damaged Brian’s hearing with a blow to the head and whose legacy of greed and spite screwed the boys out of potential profits.

He tempers his arrogance and ill will with a genuine passion and a sense of grievance. And he sweetens the corrosive bitterness that seasons the memoir with mea culpas, the quest for spiritual enlightenment and the concern for the environment as well as his undiminished appetite for performing.

Scariest of all is their skirmish with Charles Manson, who saw them as a route to his own musical career.

It’s a proper, no-holds-barred romp through the life and times of the greatest US rock band to surf the planet.

Neil Norman

Talking Story With Mike Love of The Beach Boys

“Catch a wave and you’re sitting on top of the world.”

That’s exactly where Mike Love, founding member and lead singer of The Beach Boys, is today. It’s been 50 years since the mega-hit “Good Vibrations,” widely considered one of the greatest masterpieces in the history of rock ‘n’ roll, made its debut on Oct. 10, 1966. The Beach Boys perform on the Big Island at 7 p.m. Sunday at the Hilton Grand Ballroom in Waikoloa.

West Hawaii Today had the opportunity to speak with Love about the upcoming performance and his new book being released later this year.

Arguably the most popular American rock band of all time, The Beach Boys appeal is multigenerational with more than 50 top singles and a career lasting well over five decades. With The Beach Boys being such an integral part of American culture and history, Love remains current on contemporary artists and spoke about one performer in particular that he admires.

“One of my favorite contemporary performers is Bruno Mars,” said Love. “I like the way he does classic, old-style rock ‘n’ roll. All his songs have melodies and arrangements — that’s the kind of music I can relate to. In regards to The Beach Boys’ influences, there were The Everly Brothers and their harmonies, Chuck Berry and his guitar licks, and of course the doo-wop groups. The Four Freshman had sophisticated and somewhat complicated harmonies. Not everyone can harmonize like that, but this was the kind of sound that distinguished The Beach Boys.”

“Before we were the Beach Boys we sang as family members at church youth nights and family get-togethers, whether it be Thanksgiving, Christmas or birthdays. There was always harmonies. We loved to get together and each person would pick out a part and sing it. My cousin Brian had the high falsetto thing down and I would sing the bass part. My family was very musical. It’s what we had and it’s what we loved.”

Love is grateful that he lived through the musical decade of the ‘60s. When asked which musical era he would most like to be part of, he didn’t hesitate.

“The ‘60s was such a rich time in terms of songwriting,” he said. “Not only did you have the Beach Boys, but you had the Beatles and of course the Rolling Stones, but you also had Motown. And MoTown, for crying out loud what a great roster they had—Marvin Gaye, The Supremes, The Four Tops, The Temptations, Stevie Wonder, Smokey Robinson, so many fantastic artists. That time period for me, was the most rich in terms of diversity and pure songwriting. I think the ‘60s was the best decade for music, that’s just my personal opinion.”

“That’s a good question,” said Love. “You know a lot of times we’ll play a song that doesn’t resonate with the crowd as much as another song. We found by trial and error which songs are the best, and every night we try to structure the flow of the concert so each song supports the next. In other words, we don’t do all up-tempo songs, or all ballads. We structure the selections so we may sing a slow song like ‘Surfer Girl,’ and the next song might by be ‘Don’t Worry Baby’ which has a bit of a tempo to it. Then we might do ‘Little Deuce Coupe’, ‘409’ or ‘I Get Around.’ We’ll progressively step up the tempo, then we’ll drop it back down again. There’s a sort of a flow to the concert so it’s not boring and it’s not the same sound or the same tempo. It also depends on the venue. If we’re performing somewhere more intimate we can play something more subtle or more artistic. Of course we always do our hit songs like ‘Kokomo,’ ‘California Girls’, ‘Help Me Rhonda’ and ‘Good Vibrations.’”

Love’s new book, “Good Vibrations, My Life as a Beach Boy” will hit bookstore shelves later this year. It will be the first time Love is able to tell the story in his own words.

“There’s been lots of words written about The Beach Boys — whether it be about the musical aspect, the more notorious aspects of my cousin’s life, or Charles Manson (for a time the Manson family was living in cousin Dennis Wilson’s house), but there’s never been a book by me,” said Love. “I’ve never come out with my story, which is a shame because there are misconceptions and outright fallacies that have existed. Now I’m able to address them. Not by virtue of trying to correct inaccuracies, but just telling my story — the way things unfolded and the way things happened from my point of view. I think it’s important, not for me so much because I know what I did and I know what I went through, but for my children and my grandchildren, and for fans that are interested in the story of The Beach Boys from the person who has been there from the beginning.”

When asked about what inspires him to get out of bed everyday and keep making music, Love expresses appreciation for the blessings his career has bestowed upon him.

“We are very blessed to do what we do,” he said. “What was originally a family hobby — singing and putting harmonies together for the joy of getting together and creating music, became a profession. We didn’t come from wealth, our wealth was in the music. That makes us some of the most fortunate people around. We get to travel the world, perform our music, and have it appreciated by people five decades later. That’s what really inspires me. If you’re a musician and a performer that’s what you like to do. It’s our pleasure to come out on stage and do our shows. That’s what inspires me on a daily basis. It’s pretty phenomenal.” ■

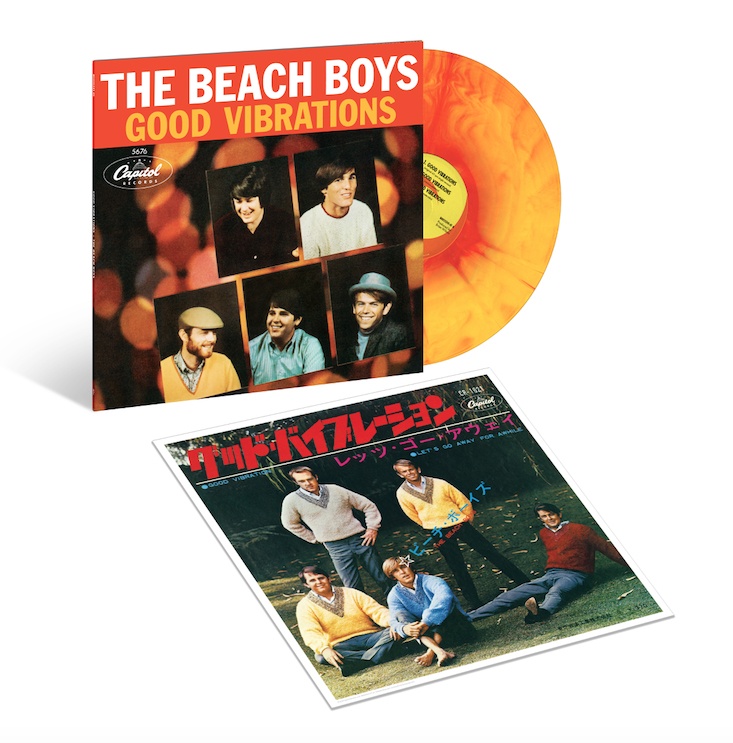

Celebrating 50 Years of “Good Vibrations” With Commemorative Sunburst Vinyl On October 7

THE BEACH BOYS CELEBRATE 50 YEARS OF “GOOD VIBRATIONS” WITH COMMEMORATIVE SUNBURST VINYL

October 10th marks the 50th anniversary of the release of one of popular music’s most iconic songs of all time, The Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations.” The Beach Boys and Capitol/UMe will celebrate the golden milestone with the worldwide release of “Good Vibrations” (50thAnniversary Edition) on a 12-inch sunburst vinyl EP on October 7. Named the “Greatest Single of All Time” by MOJOmagazine, “Good Vibrations” is a musical treasure for the ages.

Recorded across several sessions at four Hollywood studios between February and September 1966, “Good Vibrations” was a revelation upon its release, wowing musicians, critics and music fans and rocketing to the top of singles charts around the world. A crown jewel of popular music, “Good Vibrations” has been called a “pocket symphony,” with its still-innovative production, lush, layered arrangements and range of instruments, including the world’s most celebrated use of the theremin.

The “Good Vibrations (50th Anniversary Edition) vinyl EP features the original 7” single version, an alternate studio take, an edit of the song with elements from various sessions, an instrumental, and a live version from a Honolulu rehearsal in August, 1967 that was originally intended for the lost album Lei’d in Hawaii, plus the single’s B-side, “Let’s Go Away For Awhile.” A pull-out lithograph of the single’s original Japanese cover art, with its “Good Vibration” title typo intact, is included in the EP package, which features the original 1966 U.S. single cover art on its front.

Fans in North America and the U.K. are invited to share their “Good Vibrations” with The Beach Boys for a chance to be featured in a special 50th anniversary tribute video. For more information, visit http://TheBeachBoys.com/goodvibrations.

2016 is a golden year for America’s Band. In June, The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds (50th Anniversary Edition) was released worldwide in several configurations, including a 4CD/Blu-ray Audio collectors edition presented in a hardbound book, featuring the remastered original album in stereo and mono, plus hi res stereo, mono, instrumental, and 5.1 surround mixes, session outtakes, alternate mixes, and previously unreleased live recordings; a 2CD and digital deluxe edition pairing the remastered album in stereo and mono with highlights from the collectors edition’s additional tracks; and remastered, 180-gram LP editions of the album in mono and stereo with faithfully replicated original artwork.

Fans in North America and the U.K. are invited to share their “Good Vibrations” with The Beach Boys for a chance to be featured in a special 50th anniversary tribute video. For more information, visit http://TheBeachBoys.com/goodvibrations.

Led by founding member Mike Love, The Beach Boys are on tour all year, celebrating the 50th anniversary of “Good Vibrations.” Founding member Brian Wilson is also on tour, accompanied by founding member Al Jardine, performing Pet Sounds live for the last time. New memoirs by Love and Wilson will be published this fall.

The Beach Boys continue to hold Billboard / Nielsen SoundScan’s record as the top-selling American band for albums and singles, and they are also the American group with the most Billboard Top 40 chart hits (36). “Good Vibrations” was inducted into the GRAMMY Hall of Fame® in 1994. ‘Sounds Of Summer: The Very Best Of The Beach Boys’ has achieved triple-Platinum sales status and ‘The SMiLE Sessions,’ released to worldwide critical acclaim in 2011, was heralded as the year’s Best Reissue by Rolling Stone and earned a GRAMMY Award® for Best Historical Album.

Preorder “Good Vibrations” (50th Anniversary Edition): http://smarturl.it/GoodVibrations50

The Beach Boys: “Good Vibrations” (50th Anniversary Edition) [sunburst vinyl EP]

SIDE A

1. Good Vibrations (original 45 rpm single version)

2. Good Vibrations (various sessions)

3. Good Vibrations (alternate take)

SIDE B

1. Good Vibrations (instrumental)

2. Good Vibrations (live concert rehearsal: August 25, 1967)

3. Let’s Go Away For Awhile (original B-side)