Inside the Ambitious Plan to Monetize the Beach Boys’ Legacy

Brian Wilson, Mike Love, and Al Jardine on why they’ve sold a controlling interest in their intellectual property to a new company led by Irving Azoff — and how they hope to celebrate their 60th anniversary

By Patrick Doyle 2/18/21

When Carl Wilson died of cancer in 1998, his sons Jonah and Justyn became heirs to their father’s estate. That meant joining with surviving Beach Boys founders Mike Love, Brian Wilson and Al Jardine to vote on key business decisions, from archival releases to commercials. It wasn’t easy. “The dynamic changed a lot after our father passed,” says Jonah, who was in his late twenties at the time. “Not to say it was all negative, but we had a lot of challenges.” Adds Justyn, “In the beginning, it was just trying to navigate a very complicated group of individuals.”

These days, Carl’s sons are more optimistic. They recently came together with the founding members to make a major decision: The band has sold a controlling interest in the Beach Boys’ intellectual property — including their master recordings, a portion of their publishing, the Beach Boys brand, and memorabilia — to Iconic Artists Group, a new company run by longtime music business power player Irving Azoff.

“They can make the final decision on business decisions, which is what we really need — what we have needed, I should say,” says guitarist Al Jardine, who, with the rest of the band, will retain an interest in their assets, participating in the “upside” that Iconic expects to create by actively marketing and promoting the Beach Boys.

Azoff has managed the Eagles since 1974, and his clients also include Steely Dan, Jimmy Buffett, and Jon Bon Jovi. His Azoff Company has artist management, music publishing, and venue branches, but he is launching Iconic as he contends with a new reality: What happens when artists can no longer tour to support themselves? “A lot of his artists are getting to a point in life where they want to think about estate planning, they want to think about the future of their legacy,” says Elizabeth Collins, co-President of the Azoff Company. “We’re not replacing anybody’s manager by any stretch of the imagination, but oftentimes, their manager is their same age.” (Azoff, 73, expects Iconic to continue long after he stops managing artists.)

Iconic will bring the Beach Boys’ music, branding, archives, and more under one roof, unlike recent deals struck by Bob Dylan , who sold his songwriting catalog to Universal Music Publishing Group for a reported sum of nearly $400 million, and Neil Young, who sold half of the worldwide copyright and income interests of his catalog to Merck Mercuriadis’ Hipgnosis Songs Fund for an estimated $150 million. “The fact that they’re buying not only music rights, but also rights and in name, image and likeness and brand — I think it makes their strategy somewhat unique,” says David Dunn, an investment banker who has worked with the estates of Prince and Michael Jackson. “I think their strategy is interesting, because they’re trying to develop the overall brand along with the music assets.”

Azoff, who is not disclosing how much his company paid for a controlling stake in the Beach Boys organization, sees Iconic as filling a crucial role absent in other recent deals. “Most of those are being set up as financial transactions that are more financial-institution-feeling,” he says. “We like to think that we have a particular talent from having represented people like the Eagles and Fleetwood Mac and Van Halen and Steely Dan all these years to really, really understand longevity and how to build it, and we’re going to be thrilled to help the Beach Boys achieve all these goals.”

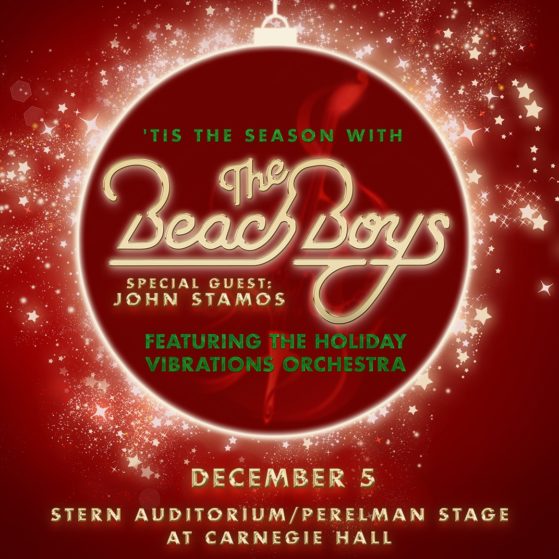

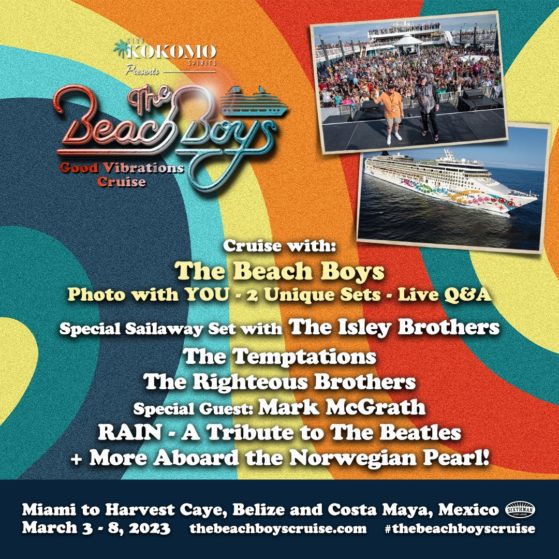

The first order of business is celebrating the 60th anniversary of the Beach Boys’ founding in Southern California in 1961. Potential plans include a documentary, a television tribute special, a touring exhibit, and more — and maybe, if everything lines up just right, their first reunion shows in nearly a decade. “I’m humbled and honored that they chose us,” says Azoff, who saw the band play when he was a teenager in Illinois in 1965, an experience he calls “mind-blowing.” “It all started for me there,” he says. “We understand the responsibility that they’ve assigned to us and we will not disappoint them. We’re gonna get this right.”

The history of the Beach Boys’ business side is full of missed opportunities. In 1969, Murry Wilson, the domineering father of Brian, Dennis, and Carl Wilson, and the band’s former manager, sold Sea of Tunes — the band’s publishing company, which owned the rights to the dozens of classic hits from “Surfin’ Safari” to “Good Vibrations” — to A&M Records for only $700,000. “He believed we were washed up,” Brian wrote later. “He had taken the only thing that we knew would last, our songs, and sold it off like he was running a garage sale.”

Those songs, singer Mike Love wrote in 2016, might be worth $100 million or more today. Love believed that the lowball deal caused a “ripple effect” for the rest of the Beach Boys’ career. Band members retained their own managers, and often battled each other in court. In 1989, Brian sued A&M to reclaim the copyrights, asking for $100 million in royalties; the case was settled out of court. In 1994, Love sued Brian for co-writing credit on dozens of songs, and won.

These and other disputes have mired the band in conflict over the years. For much of the past two decades, Love and Wilson have toured separately — Love under the Beach Boys name, Wilson as a solo artist. While it’s been confusing for casual fans, the arrangement has worked for the Beach Boys organization. “Not to sound corny, but as long as the music’s being played for audiences and they’re enjoying it…that’s really the thing to celebrate,” says Justyn Wilson.

Through it all, the band has struggled at times to capitalize on its fame and acclaim. “We’ve gone through a few fortunes, believe me, with different organizations,” says Jardine. He mentions a short-lived Beach Boys Cafe in Manhattan Beach in the early Nineties, and a long-forgotten clothing line. “We got totally destroyed,” he says. “These things come and go and come and go, and after a while, you’re like, forget about it, who needs it?” Love echoes the point: As he puts it, “I think we’ve been great in music, but maybe not as great as we could be in furthering our brand.”

For Iconic, that means a chance to do better with a name that’s been long undervalued. “In a lot of ways, they were what Jimmy Buffett did with Margaritaville before Margaritaville. It just never got done,” says Olivier Chastan, Iconic’s CEO. “The Beach Boys, in a sense, are not just a band. They’re a lifestyle. They’re a consumer brand. And they’ve never really exploited that.”

Chastan remembers vacationing in France a few years ago, when he was working as a consultant for music publishing firms and investment funds. “I was walking down the street, where you have all the big brands, like Hermès and Louis Vuitton, all these iconic French brands, and wondering, how can they make it work where people still want to pay $10,000 for a handbag, and the brand is 200 years old? What are they doing that we’re not doing? It was really taking these brand management concepts, and seeing, how do we apply them to the music business in general?”

Azoff was thinking about the long-term future of his artists, too. He and Chastan met shortly after the death of Tom Petty, which had resulted in a bitter estate battle between Petty’s daughters, Adria and Annakim, and Petty’s widow, Dana. “It was really through a discussion around: What happens when something as tragic as the death of Tom Petty [happens]?” says Chastan. “And you’ve seen plenty of examples of fights around the artist, [like] the estate of Aretha Franklin. What we offer is a way to totally bypass some of those issues.”

Chastan met with the Beach Boys, pitching them on a partnership that included two goals: brand development and brand monetization. With development, they would aim to reintroduce the group to new listeners through social media, radio, YouTube, and more. With monetization, they would leverage the Beach Boys’ music, brand, video content, and memorabilia for film placement, documentaries, biopics, touring exhibits, and more.

Not everyone in the music industry is on board with the current gold rush in catalog sales for legacy acts. Pop hitmaker Dianne Warren recently said on the Rolling Stone Music Now podcast that selling her songs “would be like selling my soul, and that’s not for sale”; other industry players have issued warnings about moving into “a world of finance that lacks a certain amount of discipline.”

But the Beach Boys would rather focus on the upsides of giving Iconic control of how their name and music are used. “They want to preserve the legacy, and if they want to do a little branding, it would be fun,” says Jardine. “I’d like to have some fun, you know? You get to a point where it gets really serious, the business of having a legacy. Maybe we’ll have a little theme park somewhere, or, I don’t know, restaurants. I always wanted to have a Beach Boys restaurant somewhere.”

Love, for his part, is characteristically cheerful about it all. “This partnership will expand the potential of everything,” he says. “No stone will be left unturned.” He likes the idea of a stage production: “There can be a musical on Broadway, things that we haven’t done yet,” he says. “Look at what happened with the Four Seasons and Jersey Boys, a huge success around the world. There’s no reason why the same couldn’t be true of the Beach Boys.”

The deal does not give Iconic ownership of much of the Beach Boys’ Sixties material, which is now owned by Universal. “Yes, the rights are split — it’s not the end of the world,” says Chastan. (“We have the original recordings, and we have the publishing, but our ability to do the most with this band relies on the ability to work with the band,” says Bruce Resnikoff, president/CEO of Universal Music Enterprises. “Iconic will represent the band in a way that will only enhance, I think, the value for everybody.”)

Chastan gets most excited talking about the Beach Boys’ brand and future tech possibilities. “That includes VR, AR, 3D, CGI, natural language processing, et cetera,” he says. “That, to me, is probably the most interesting aspect of what’s going to transform our business. In five years, I could send you a text and say, ‘At 2 p.m., let’s put our Oculus Rift glasses on, and let’s go see the Beach Boys record ‘Good Vibrations’ at Western Recorders.’ ”

The CEO continues: “The studio is still there, so we could 3D scan the studio. The Beach Boys’ faces can be digitally replicated pretty easily. You’ve seen it with that Scorsese movie [The Irishman], where he did the de-aging technology. You’ve got natural language processing, which gives you the technology to actually have a conversation. So we could be witness to history from our couch.”

Chastan recently visited with Love in Lake Tahoe, where he looked at old memorabilia. “One thing that Iconic offers, which is absolutely unique, is that we’re a partner while they’re alive to actually help them shape that legacy, which they can’t do once they’re gone,” says Chastan. “How you want to be remembered? How you want to see your legacy in the future, even when you’re not there?”

Love even says there may be a day when the Beach Boys are touring long after he stops singing. “As long as it’s presented beautifully and authentically,” he says. “The beauty of music is, even though the originators might not be there anymore, the music can live on for centuries, as you know from the classics. Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, you know?”

While the Beach Boys are game to talk about their legacy, they’re even more eager to talk about their immediate future as a band. Their 50th anniversary ended messily: In 2012, they reunited for a new album and a successful tour, but by 2013, Love was touring under the Beach Boys name without Wilson or Jardine. “It sort of feels like we’re being fired,” Wilson said in a statement.

Now, a day after receiving the first dose of the Covid vaccine at Dodger Stadium, Wilson sounds upbeat. He says he misses touring, and he’s been staying in shape by walking in the park “every goddamn day” and working with his vocal coach three times a week. “We did 20 songs today,” he says. “My voice is sounding really good!”

The possibility of marking the band’s latest milestones appeals to him. “I want to make the 60th anniversary a big celebration,” he says. “We’re thinking it might be cool to have a restaurant and some stores to sell cool Beach Boys stuff.” Most exciting to Brian is the idea of touring and possibly recording with the group he founded in his parents’ living room six decades ago. “It’d be a great trip, a big thrill,” he says. “When we went on tour for the 50th anniversary we had so much fun. It’d be such a joy to be singing with the boys again.”

As for when such a tour could happen, given the realities of the pandemic, Azoff says even he doesn’t know. “We’ve got lots of experts and everything weighing in,” he says. “Anybody that tells you they know is guessing. This latest surge really frightened people. I really hope that the fall is good… I’m hopeful for the fourth quarter, but I’m less hopeful for the summer now.”

When tours do start up again, Love says the new business arrangement will not affect his ability to tour under the Beach Boys name. “I think that that remains the same,” he says, but adds he is also open to a reunion with the other founders. “I wouldn’t rule anything out.” One thing he’s not thinking about is retirement. “I feel pretty darn good,” Love says. “I’ll be 80 years old March 15th, but I’m not like the normal 80-year-old guy, because [of what] we do on stage. It’s like youth serum or something.”

Jardine had been touring with Wilson’s band before the pandemic hit, but he also regularly talks to Love. “We don’t discuss business much,” he says. Jardine tells a story about the other day, when he went to his basement and put a Chuck Berry 78 on the jukebox. Soon, he’d picked up his bass and was playing along. “I suddenly I felt like I was on the road again. It was the best feeling. So I called Brian right away. And I said, ‘You won’t believe this.’ I said, ‘It was just like the old days, when we were all playing together.’

“And there was this long silence,” says Jardine. “And then Brian says, ‘I gotta go now.’ ” Jardine laughs. “And that’s okay. Because at least we connected, you know? It was nice to be able to call my old friend and partner and share that.”

Inside the Ambitious Plan to Monetize the Beach Boys’ Legacy